Russian psychiatrists again question findings by Belarusian doctors in case of Maladechna resident

As a result of misunderstanding in 2012, a resident of the town of Maladechna, Alesia Sadouskaya, was taken to the police station, where law enforcement officers reportedly tortured her using so-called “lastochka” position, as her hands were cuffed behind her back and tied to her feet, while the woman was put on the floor with her belly down. After Ms. Sadouskaya threatened to sue the policemen, she herself was accused of an offense and later sent for a psychiatric examination. As a result, a commission composed of psychiatric experts concluded on the need of compulsory treatment.

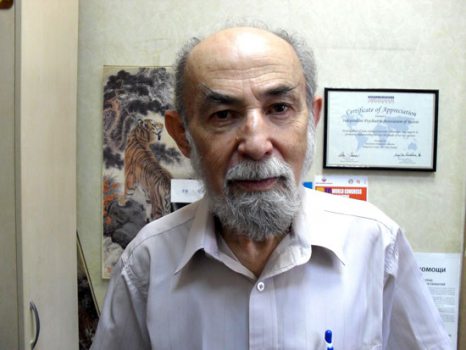

This decision was challenged in court, which appointed another examination. Not trusting the Belarusian doctors, on the eve of the re-examination, she passed an examination in Moscow, in the Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia (NPAR). The survey was made possible thanks to the support from the Mahiliou Human Rights Center Group and the Human Rights Center “Viasna”. NPAR President, coordinator of the working group of the Expert Council under the Commissioner for Human Rights in the Russian Federation, Yuri Savenko commented on Alesia Sadouskaya’s case and gave an exclusive interview to the HRC “Viasna”.

- Yuri, Belarusian human rights defenders wonder whether Alesia Sadouskaya needs treatment?

- Definitely not. Having examined Sadouskaya, we can say that this requirement looks absolutely ridiculous and inconsistent with the things that are literally on the surface. The person as always been successful socially and active. But, obviously, she was not afraid to fight back the policemen and they, fearing complaints from higher authorities, have been trying to extinguish this case by their methods.

I would call Ms. Sadouskaya’s typical. In most such cases, which, unfortunately, are many in Russia, too, people who fall foul of the police or authorities are always to blame. Law enforcement agencies are trying to hush up such cases, and psychiatry, unfortunately, often goes to help them.

- Belarusian human rights defenders, infinitely trusting psychiatrists, not immediately took the side of the victims – in our case, Ihar Pastnou and Alesia Sadouskaya. How should we address this issue?

- It is important to understand that human rights activities are by themselves a kind of a spiritual ideology. And psychiatry, psychopathology analysis do not give medical value to the activities – and it’s wrong. Spirit does not get sick, that’s why human rights activities can be successfully, properly and honestly pursued by people with any diagnosis.

In reality, we see that human rights activities involve people who were either hurt by the authorities or having such a character that they are not able to stand injustice – they “explode”. And here is an old word “psychopathy”, which was replaced with a “personality disorder” – there are 10 types of it. Or with acute psychopathy it can be equated to a serious mental disorder. Let me explain with an example.

During the Civil War this diagnosis saved people from executions, and psychiatrists were increasingly using this diagnosis to save people from death. In the 1920s, Gannushkin in his textbooks called to recognize insane people with psychopathy and affective reactions, and it was highly humane. And since 1936, the Second Congress of Russian psychiatrists told in its resolution to “consider an expansive diagnosis practically and theoretically harmful”. But the war was over, and when the human rights movement was born, the green light was given to the scientific school, which again treat diagnoses more widely. But they already had another meaning – it was a way to discredit or intimidate human rights movement. That is, over time, everything turned upside down several times.

- So what’s the problem now?

- We must understand that there are a lot of compulsive people among psychiatrists, and the higher the position, the more “chains” they have. And we do not index it and condemn colleagues who are forced to do such things. We condemn the social atmosphere that makes professionals conform with sometimes criminal decisions of the government.

- Psychiatrists have a joke: There are no healthy people, there are badly examined ones. After the incident with Ihar Pastnou, who was the first to be examined by you, there were opinions saying that every person face a diagnosis. Is this true?

- There is ICD-10 – the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems in its 10th revision, it concerns the whole of medicine. Psychiatry is covered in section number 5. And it is psychiatry only that says “disorder” instead of “disease”. And the concept of disorder is broader: it includes both mental illnesses and pathology, i.e. deviations – deviation from the norm, but it is not a disease. Pathology – it’s either a whole motley set of pathological characters (“acute” characters) up to standards, as there is a continuous scale of transitions; or intellectual impairment, also of varying degrees and forms, with 500 varieties.

As for Ihar Pastnou’s case, I must say that everything he does is highly productive, socially useful, and it is the tolerance with which reacted to the repressive measures against him that is not the norm. That’s really pathological.

- Can an ordinary person determine whether the person he is talking to is sick?

- The thing is that everything changes on the fly. Speaking about the Belarusian cases, we realize that people are in situations of stressful and traumatic nature. And if a person has some type of acute character, he goes his own way – sharpened, heating up and decompensating. And it turns out that the situation itself and all its actors provoke and unwind it instead of doing exactly the opposite.

I stress that each person is classified separately in respect of mental illness – sick or healthy, and separately – with or without pathology (i.e., he is normal or with deviation).

If a person is sick, there is a subclinical level, when it is not necessary at all to appeal to the doctor, and you can do with home means. There is a non-psychotic clinical level, and there is a fundamental one – the transition to a psychotic level. That’s when they say “psychotic”, then treatment in a hospital is required. This is a very important decision and it is taken by graduation.

(Psychotic disorders are severe mental disorders that cause abnormal thinking and perceptions. People with psychoses lose touch with reality. Two of the main symptoms are delusions and hallucinations.)

- And how do diseases get in the ICD? Is it true that psychiatrists vote for illnesses?

- This is a complex procedure that is preceded by long-term and painstaking joint work. All the leading psychiatrists from different countries are gathered to discuss what should be considered a disease and actually vote. But I think it’s a bad option. I think that the classification should be done by a small group of the most advanced psychiatrists in the world. A democracy in this case, that is, voting, it is not science.

- Thank you for the interview.